Museums…

Everyone loves museums.

Maybe not everyone, but let us face it, it is pretty much the first thing you will see in any country you happen to be visiting. Unless they have some sort of grand monument to boast of. Small artefacts are fine, but nothing beats monuments.

In addition to anthropology, I am also studying archaeology, so you can probably guess that I love museums sincerely and truly. Recently, however, I began (largely due to the lectures I had on my course) to think a bit more about what exactly these are. What is the difference between a museum and an art gallery, for instance? Someone at one of my introduction to material culture tutorials mentioned how a gallery was a grown-up version of a museum. Surely, if you compare this:

Fig. 1 Natural History Museum, London, UK

and that:

Fig. 2 National Gallery, London, UK

such a conclusion is justified.

And yet go to any museum nearby and you will be much more likely to find adults walking around the showcases, with perhaps a couple toddlers running around or sitting grimly by the wall (or commenting on the oversized busts of the Venus figurines).

Same, of course, applies to art galleries. There is not much difference between the target audience. Exhibitions targeted specifically at children, such as some of these at the Natural History Museum, are an exception rather than a rule.

And here comes the question again - what is a museum? What are its purposes? Why do we even bother with these dusty, melancholic rooms, full of artefacts removed from their context and narrative, existing 'out of time' and hence impossible to fully interpret (Shelton 2006, 485)?

Below you will find a critique of a certain exhibition which, hopefully, will answer some of these questions.

***

Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

Permanent Exhibition

The exhibition I have chosen for this exercise is the permanent one at

the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London. What I find particularly

interesting about it is the fact that it was established as a part of the

University College London’s Department of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology

and was to be first and foremost a teaching resource. While usually museums can

be either described as fulfilling the funciton of educating general public that does not have any

specialised knowledge on a given subject, it is not the case of the Petrie

Museum. A teaching collection is primarily used by people with some sort of

academic background, so the objects do not require as much explanatory

information as in case of a museum. Furthermore, attracting a visitor is not a

top priority.

Nowadays, however, the Petrie Museum does not function merely as a

teaching and research resource. It hosts the fourth largest collection of

Egyptian artefacts in the world and is open to the general public as well as to

the academics. The central point of this text will be whether it fulfills the

educational function of a museum well.

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology is located on Malet Place in

Central London. It is a rather small street that forms a passage between

various UCL buildings. As it is framed by iron gates on both sides, it may not

be the most inviting place for someone who is not familiar with the

surroundings (such as a tourist, as opposed to a UCL student or academic).

Fig. 3 Iron gate separating Malet Street and Malet Place

The building itself is not an impressive one, either – compared to

large, world-reknown museums such as the British Museum, the Louvre or the

Prado it lacks the monumental features typically associated with such institutions. Furthermore, it does not differ much from the surrounding ones and

is annoted only by a relatively small plaque. Although it is more prominent

than these used to mark other university-related spaces, such as lecture

theatres or cafes, it is by no means easy to spot. I have to admit to having

missed it the first time I visited.

Fig. 4 Petrie Museum's facade - not quite as impressive as…

Fig. 5 … the British Museum's facade

To enter the actual museum one has to climb the stairs, however the way

to the galleries is clearly marked. Upon entering, one sees a small reception

desk. I have visited the museum three times and it has never been overtly busy

– as a result the receptionist usually greets the visitors, offering a free map

and answering eventual questions. Although the location of the museum may

negatively influence its accessibility, such a welcoming attitude is a

surprising change from the formal and imposing atmosphere of many larger

museums.

Fig. 6 Museum's plan - you will notice the place is rather small

The gallery itself, however, is very quiet. People hardly ever make any

comments and if so they are likely to whisper. Furthermore the general nature of

these appears to be academic, which I suspect is caused by the specific theme

of the place. As all the objects in the museum are related to Egypt, chances

are any visitor will have some interest in the subject, which would imply at

least some rudimentary knowledge. It is in stark contrast to more generally themed and interactive museums – the Natural History Museum in London or the

Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw, with many activities designed primarily

for children, are only two examples. Other large museums, even if not so

strongly adjusted to younger visitors‘ needs, tend to enjoy more casual

atmosphere, presumably because of the sheer number of visitors, most of whom tend to be relaxed tourists.

I would not consider the serious atmosphere a flaw as it clearly stems

from the very nature of the exhibition, furthermore it aids focusing on the

artefacts. However, the way in which the objects are displayed appears more suitable for a teaching collection than an actual museum exhibition. They are generally grouped by category (e.g.

pottery, flints, writing samples) and within such sections ordered

chronologically. Hardly any objects are particularly emphasized – the

instrument pictured below is a notable exception, furthermore one can play on

it which adds to the museum experience.

Fig. 7 A reconstruction of an ancient instrument - the visitors could actually play it

Overall, however, the artefacts are presented in more or less the same

way. As a result objects as common as flint scrapers tend to be placed next to

wooden spearheads, extremely rarely preserved as wood decomposes easily. There

is no distinction made between these, which makes them harder to appreciate for

a layman. Furthermore, some unique artefacts, such as the oldest preserved

papyrus (again, a very fragile material) sandals are not annoted at all. Such a

layout is very clear and probably helpful if one looks for a specific kind of

artefacts. However this is more likely to be the case of a student or academic,

as opposed to the regular visitor. It suggests that the exhibition may not have

been much rearranged since its primary purpose was to serve as a teaching

collection.

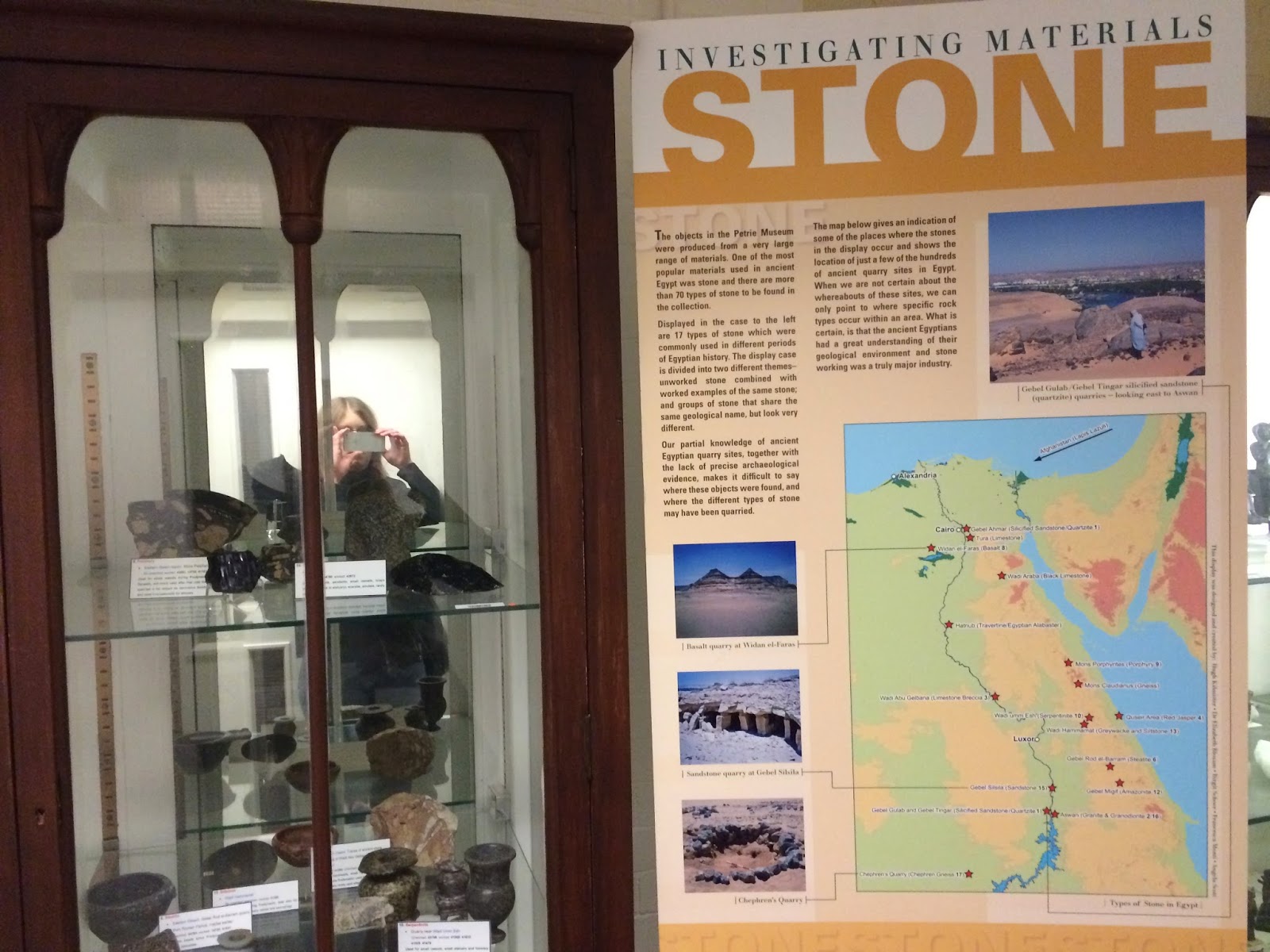

Fig. 8 The showcases

Fig. 9 More showcases

Arranging the artefacts according to their function and period does, however, situate them in a historically accurate context. Recreating the past is impossible, but even an approximation of an object's cultural context is more helpful in understanding its meaning than embracing this inability and treating it as primarily a source of contemporary interpretation. Attempts at doing so do not necessarily prove succesful.

Such was the case of the Quai-Branly, whose director’s attempt at making the

museum client the first interpreter of an artefact prompted rather mixed

reactions (Kimmelman 2006) (Naumann 2006) (Clifford 2007).

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology avoids such pitfalls, clearly

defining the historical context at least of the collection as a whole.

Furthermore, there are elements which provide more insight into given artefacts

– plaques, leaflets, reconstructions.

Fig. 10 A very colorful explanatory note

Fig. 11 This reconstruction is supposed to enhance the viewer's understanding of the ancient Egyptian transport

Although its past as a teaching collection

is visible, the staff are trying to turn it into a museum equally enjoyable for

an academic and a layman. I spoke to a volunteer responsible for

digitalising the Petrie Museum’s resources, and she told me that they are

constantly trying to come up with new ideas on how to engage the public with

their collection. Another volunteer was always around, answering any

questions and explaining the historical context. This added to the exhibition,

making it not only a collection of artefacts, but a space where one could

actually engage with history and satisfy their curiosity – exactly what a

museum should be.

***

So does this answer any of the questions posed above? I would argue it does. The Petrie Museum provides one with just enough information to grasp some aspects of the ancient Egyptian civilization even if they have no previous knowledge. On the other hand, the artefacts are laid out neatly and clearly, and if someone with some background in the subject seeks specific information, they should have no trouble finding it. In other words, the museum educates - which is exactly what it should do. This is where a museum differs from an art gallery, which is more concerned with the aesthetic aspect. At an art exhibition the way the works are presented can be a form of art itself - but in case of a museum that is not necessary. I would argue it draws one attention from the fact that the objects presented are (almost always) pragmatic rather than aesthetic - and even nowadays they serve a practical purpose, helping recreate the past. Coming back to Quai Branly - it is an example of a museum whose curator did not take that difference into account, treating culturally pragmatic artefacts as objects of art. The curators at Petrie stood clear of this error.

These, of course, are all my opinions. What do you think? Do you agree? Or would you rather say I am silly and completely misunderstand the concepts? Please, share your thoughts!

Bibliography:

Clifford, J. 2007. Quai Branly in Process. In: MIT Press Journals, No. 120, pp. 3-23.

Kimmelman, M. 2006. A Heart of Darkness in the City of Light. In: New York Times, 02 July 2006.

Naumann, P. 2006. Making A Museum: "it is making a theater, not writing theory". An interview with Stephane Martin, presidentdirecteur general, Musee de Quai Branly. In: Museum Anthropology, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 118-127.

Shelton, A. A. 2006. Museums and Museum Displays. In: Tilley, C. (ed.), Handbook of Material Culture. London: Sage, pp. 480-499.

No comments:

Post a Comment